For many centuries, nobody wanted a clock. You have up at sunrise to tend your subjects, work in your tannery, etc.. Then you moved home, and if it got dark, possibly after ingestion and an hour conversation around the fire, then everyone went to sleep.

Century B.C. Water at a boat has been allowed to escape through a pinhole at the floor, the amount of water and dimensions of this hole ascertaining how much time it would have to drain.

Because nobody could assess the time of day and in any situation, there could not be a universal time since there wasn't any means of comparing with different folks in their own village, much less compared to others. They could guess just how far along the afternoon was by the elevation of the sun, and about the passing of a month by the waxing and waning of the moon.

The following step was that the candle clock, which appeared in a variety of forms, starting in China in roughly 500 A.D. One kind needed a candle of understood burning speed with hours marked away on the other side, or on a sconce supporting it:

The first mechanical clocks needed a weight hanging from a pulley which turned into a targeted hand (only one, signaling hours and parts of one hour) but controlling the rate of this hands was rudimentary. Spring-wound clocks seemed in 15th-century Europe. About 1400 A.D., coiled springs started to be utilized in barrels, and lots of early clockmakers were locksmiths.

Here is something you'll discover difficult to believe. All substantial mechanical clock and watch mechanics creations weren't Swiss, but British.

Navigators had always endured great difficulty in locating their position at longitude (i.e. horizontally around the world ), the planet annoyingly rotating rather than standing still. The only way could have would be to utilize printed astronomical tables in combination with star or sun sights by sextant, but for this, you would have to be aware of the time of day to the closest moment at least, if the most precise clocks could not keep time to the closest quarter of hour-long voyages. And in any case, there was no"zero meridian" or stage on the planet where all time was quantified.

Several unfortunate disasters in the sea, brought on by poor navigation, prompted the British government to make a Board of Longitude permitted to award the massive amount of 20,000 into the first person who acquired a chronometer by which longitude may be calculated within half of a level after a couple of days.

--expired March 24, 1776, London), the son of a magician who had been a self-taught mechanic became interested in building an accurate chronometer at 1728.

Harrison finished his first chronometer in 1735 and filed it to the prize. Then he built three more tools, ever smaller and more precise than its predecessor. In 1762 Harrison's famous No. 4 marine chronometer has been shown to be in error by only five moments (0.021 levels of longitude - 1.4 kilometers ) following a ship from London to Jamaica.

Though his chronometers all fulfilled the criteria set up by the Board of Longitude, he wasn't granted any money until 1763, when he obtained #5,000, rather than before 1773 was he compensated. #20,000 in 1773 is the equivalent of roughly $2.5 million now.

The following step was to set a defining point where all longitudinal navigation will be established - it was no use saying"based on this log we might have spanned 29 miles each night" - unless there was a fixed stage from where you can chart where you had been on the surface of the world. Eventually, a global arrangement determined where the"zero meridian" could be found. Considering that the chronometer was a British creation, the place was established at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, out of London.

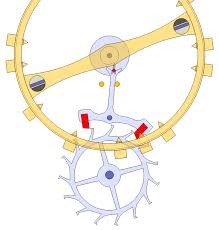

In 1755, an Englishman clockmaker, Thomas Mudge, devised one of those key and innovative apparatus in the time dimension, the lever escapement,

A kind of mechanism which just allows the mainspring to really slowly run down while moving the hour, minute, and second hands in exact fractions. It was still utilized in almost all mechanical watches, in addition to small mechanical non-pendulum clocks, alarm clocks, and kitchen timers.

Century B.C. Water at a boat has been allowed to escape through a pinhole at the floor, the amount of water and dimensions of this hole ascertaining how much time it would have to drain.

Because nobody could assess the time of day and in any situation, there could not be a universal time since there wasn't any means of comparing with different folks in their own village, much less compared to others. They could guess just how far along the afternoon was by the elevation of the sun, and about the passing of a month by the waxing and waning of the moon.

The following step was that the candle clock, which appeared in a variety of forms, starting in China in roughly 500 A.D. One kind needed a candle of understood burning speed with hours marked away on the other side, or on a sconce supporting it:

The first mechanical clocks needed a weight hanging from a pulley which turned into a targeted hand (only one, signaling hours and parts of one hour) but controlling the rate of this hands was rudimentary. Spring-wound clocks seemed in 15th-century Europe. About 1400 A.D., coiled springs started to be utilized in barrels, and lots of early clockmakers were locksmiths.

Here is something you'll discover difficult to believe. All substantial mechanical clock and watch mechanics creations weren't Swiss, but British.

Navigators had always endured great difficulty in locating their position at longitude (i.e. horizontally around the world ), the planet annoyingly rotating rather than standing still. The only way could have would be to utilize printed astronomical tables in combination with star or sun sights by sextant, but for this, you would have to be aware of the time of day to the closest moment at least, if the most precise clocks could not keep time to the closest quarter of hour-long voyages. And in any case, there was no"zero meridian" or stage on the planet where all time was quantified.

Several unfortunate disasters in the sea, brought on by poor navigation, prompted the British government to make a Board of Longitude permitted to award the massive amount of 20,000 into the first person who acquired a chronometer by which longitude may be calculated within half of a level after a couple of days.

--expired March 24, 1776, London), the son of a magician who had been a self-taught mechanic became interested in building an accurate chronometer at 1728.

Harrison finished his first chronometer in 1735 and filed it to the prize. Then he built three more tools, ever smaller and more precise than its predecessor. In 1762 Harrison's famous No. 4 marine chronometer has been shown to be in error by only five moments (0.021 levels of longitude - 1.4 kilometers ) following a ship from London to Jamaica.

Though his chronometers all fulfilled the criteria set up by the Board of Longitude, he wasn't granted any money until 1763, when he obtained #5,000, rather than before 1773 was he compensated. #20,000 in 1773 is the equivalent of roughly $2.5 million now.

The following step was to set a defining point where all longitudinal navigation will be established - it was no use saying"based on this log we might have spanned 29 miles each night" - unless there was a fixed stage from where you can chart where you had been on the surface of the world. Eventually, a global arrangement determined where the"zero meridian" could be found. Considering that the chronometer was a British creation, the place was established at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, out of London.

In 1755, an Englishman clockmaker, Thomas Mudge, devised one of those key and innovative apparatus in the time dimension, the lever escapement,

A kind of mechanism which just allows the mainspring to really slowly run down while moving the hour, minute, and second hands in exact fractions. It was still utilized in almost all mechanical watches, in addition to small mechanical non-pendulum clocks, alarm clocks, and kitchen timers.